"AN EASY MATTER FOR A STRANGER TO IMAGINE HIMSELF IN FRANCE"

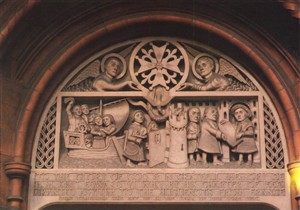

Carved relief above doorway of the French Protestant Church, Soho Square.This stone relief was erected at the church in 1950, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the opening of the first French Protestant Church in Threadneedle Street in 1550. It shows the Hugeunots leaving France, arriving at Dover and receiving a charter granting them asylum from Edward VI. This photograph was taken in about 1980.

City of Westminster Archives Centre

THE HUGUENOTS IN SOHO

By David Evans

In 1739 the Scots topographer, William Maitland, was so taken by the French presence in Soho that he wrote many parts of this parish so greatly abound with French that it is an easy matter for a stranger to imagine himself in France. Earlier, in 1720, John Strype, the historian and Vicar of Leyton, Essex, then a village five miles from London, noted that in Soho “the abundance of French people, many whereof are voluntary exiles for their religion, live in these streets and lanes following honest trades… Who were these French exiles and what were they doing in Soho?

The simple answer is that the majority were French Calvinist Protestants – popularly known as Huguenots – who had settled in the area and in other parts of Britain after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, by King Louis XIV of France, in 1685. This official decree made by his grandfather, King Henri IV, had guaranteed French Protestants the freedom to practise their faith after the long, bloody wars of religion in France. The steady erosion of their privileges had started in the 1660s and gathered speed in the 1680s especially after the king’s morganatic marriage to Madame de Maintenon (la Marquise de Maintenon) following the death of his first wife in 1683. Raised as a Huguenot and converting to Roman Catholicism in her teens, it was she, arguably, who influenced him in his decision. Thousands of French Calvinists fled the country with around an estimated fifty thousand settling in this country alone. Many were skilled craftsmen such as weavers, watchmakers, precision instrument makers, goldsmiths, silversmiths, jewellers and cabinet makers. Others brought their expertise to such professions as the law, banking, insurance and the armed forces. All of their skills were lost to France and brought to a country whose growing Empire and influence in the world benefited from this loss.

The Huguenots settled in different parts of London, notably Spitalfields to the east, but their presence in Soho can be dated to the early 1680s when they took possession of a chapel in long-vanished Hog Lane close to Denmark and Greek Streets. This had been built for Greek refugees from Ottoman persecution but which for various reasons they vacated soon after its completion. John Rocque’s detailed map of London of 1747 shows what is called the French Church near these two streets and close to what he calls Thrift Street instead of Frith Street. As Rocque had once lived in Soho – at the Canister & Sugar Loaf in Great Windmill Street – and knew the area well, was this a true mistake or was Rocque subconsciously thinking of the prudence in the use of money and other resources which formed one of the many virtues possessed by the Huguenots? Rocque – born Jean Rocque – was himself of Huguenot origin having emigrated to London as a child, with his parents, in the early eighteenth century. A modest man, he once described himself as a simple dessinateur de jardins and this is how he started his career as a surveyor of English gardens in aristocratic hands. His Chiswick House survey, 1736, is proof of this and of his continuing Frenchness as the result of his labours there was described as a plan du jardin et vue des maisons de Chiswick which can now be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 1738, the painter and engraver William Hogarth issued a series of four prints entitled The Four Times of Day with Noon showing prosperous Huguenots leaving their church in Hog Lane after Divine Service. In this they are shown in marked contrast to the group of seemingly ne’er-do-wells on the other side of the street. Interestingly, this congregation often referred to itself as les grecs in recognition of the church’s Greek origins.

At this stage, and as William Maitland found, many of the Huguenot immigrants in Soho spoke little or no English or used a mixture of both English and French. For example, around 1700 a husband and wife named Jean and Anne Gaudin described themselves as living at the rue du Moulin a Vent, Soho instead of Windmill Street. Nevertheless, in the mid-eighteenth century, the goldsmith Peter de la Fontaine gave his address as at the Golden Cup, Litchfield Street and told his public that he made and sold all manner of gold and silver plate, swords, rings, jewells etc at ye lowest prices and, earlier, the gold and silversmith Paul de Lamerie had opened his premises on Great Windmill Street, in 1713. By 1716 had been appointed goldsmith to King George I proof indeed that the Huguenot arrivals had been accepted and assimilated into the local population of Soho well before the next wave of, mostly Roman Catholic, refugees from France – the so-called émigrés – arrived after the French Revolution of 1789.

Today, the Huguenot presence in Soho is represented by L’Église Protestante Française de Londres - the French Protestant Church in London – on Soho Square which was designed in Franco-Flemish Gothic style by Sir Clifton Webb in the 1890s and is said to be his favourite work. A good deal of French can still be heard on the area’s streets too for London’s French-speaking population, as a whole, is now counted in hundreds of thousands. Their reasons for leaving France are now mainly economic rather than religious or political but it goes to prove that Soho, the City of Westminster and the entire capital are still very happy to welcome hard workers from across the Channel.